Socially Optimal Transaction Fee Mechanism Design

Quick post to share a new working paper: a short mathematical proof it is possible to have a socially-optimal and collusion-proof transaction fee mechanism. As a bonus, the paper identifies the exact technical shift required to achieve this outcome.

The paper is deliberately short (2 pages) both in a nod to Paul Samuelson’s similar 1954 paper on public goods provision, and because brevity makes the material easier for non-economists to understand.

Feedback and suggestions are welcome. I’d be interested to learn from anyone more current on public choice theory if we have any non-blockchain examples of mechanisms that evade Samuelson and Hurwicz’s impossibility conjectures by inducing competition for collection of a private payment. My suspicion is that what we have is indeed new, as prior to the invention of self-provisioning ledgers all communications channels would require a trusted third party to provision, and private provision removes non-excludability.

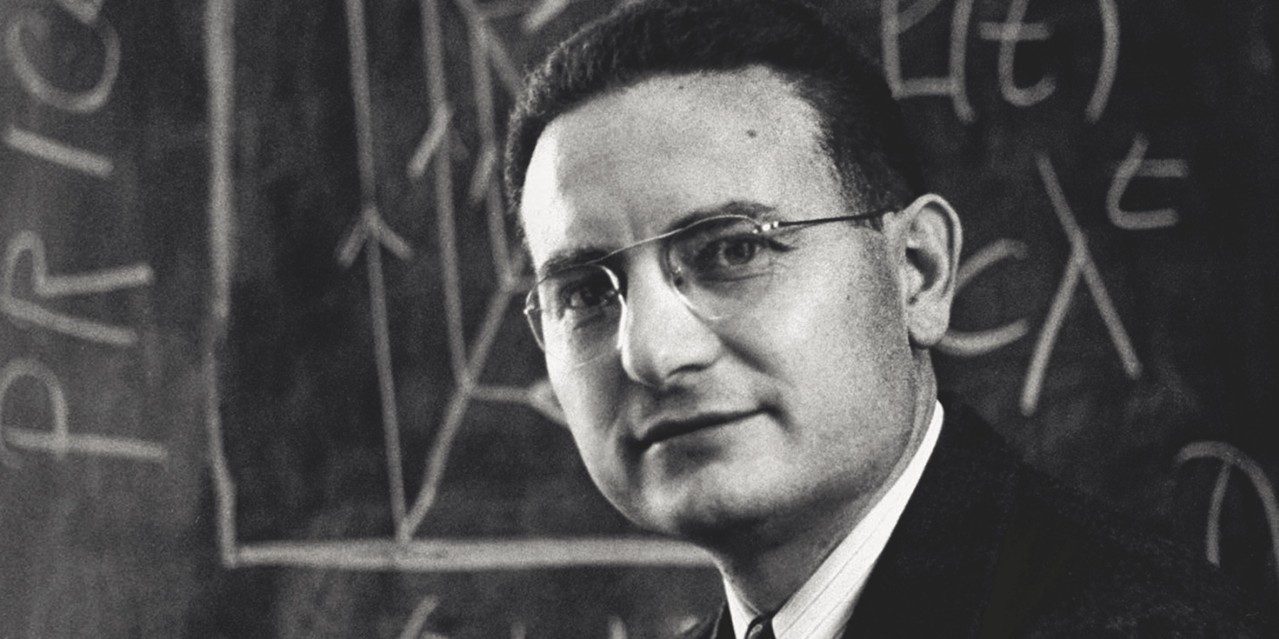

For computer scientists wandering into fee-optimization problems, I hope the paper helps understand how economics models this class of optimization problem. It is surprising how few people in distributed systems cite the work of Paul Samuelson and Leonid Hurwicz. This is particularly surprising given that Hurwicz invented the term “incentive compatibility“, authored a seminal paper on “informational decentralization” and won a Nobel Prize for mechanism design theory.

In this specific case, a lack of familiarity with their work can lead to fundamental analytic errors:

- forgetting that the token is a fungible form of value, which means that we cannot have an “optimal” transaction fee unless the user cannot get more utility from spending the same fee on other goods or services.

- not understanding that pareto optimality is a prerequisite for an incentive compatible and collusion-proof mechanism: if any subset of parties can costlessly improve their utility without making others worse off then that same group can always increase their utility by following a byzantine strategy.

- failing to differentiate between forms of collusion that lead to sub-optimal outcomes and forms of price negotiation which create optimal outcomes, which in turn indicates lack of awareness of optimal and sub-optimal market structures and collective action problems.

- incorrectly assuming that global pareto optimality (“Global SCP”) is harder to achieve than incentive compatibility (“1-SCP”), an error that seems to step from the idea it must be harder to coordinate an optimal outcome if there are more participants involved, whereas it is easier to achieve pareto optimality globally since it is a necessary but not sufficient condition for incentive compatibility, which is what is needed to make collusion irrational.

On a closing note, I believe it follows fairly directly from the work presented here that the ability of users to collude with block producers in ways that are socially sub-optimal depends on the ability of the block producer to increase their profits from another source: either free-riding on an inflationary block reward or on the unreciprocated and irrational willingness of peers to propagate unconfirmed transactions. It is possible that no mechanism with an inflationary block reward can ever be secure against collusion, as it cannot be secure against free-riding.

With luck, the issues with the way computer scientists are framing and analysing these economic problems in blockchain will self-correct as more people become aware of how powerful economic frameworks and tools are for analyzing these mechanism design problems.